First, a heads up. Next week we’re restarting with the market prediction competition. This time it’s a 10-week long competition with a grand prize of $1000 to the winner. More on that on Tuesday when the competition launches.

Now for the flavor du jour (or rather du mois).

You must have heard about the most recent stalemate in US Congress over the issue of raising the debt ceiling. Quick explanation; the debt ceiling is an imposed cap on the maximum amount of debt the US government may borrow. Lifting it does not authorize new spending but makes sure the government is able to meet previous obligations (such as the ones left over by the previous administration). It is also a tool legislators like to use to force a cut in federal spending. If the debt ceiling is breached (i.e. if Congress does not increase it), the consequences could be dire as the US credit rating would get downgraded and we’d be heading for another recession (US sovereign CDSs, going up 74% in the past month, I’m looking at you!).

Political hypocrisy and economic consequences aside, the debt ceiling - this very simple instrument of supposed fiscal prudence - is being used as a very interesting bargaining game. Again.

Let’s see if we can solve it using some basic game theory.

If you haven’t already, don’t forget to subscribe:

To remind you, we have been here before, at least twice during the Obama administration. Back then, the Republican House majority engaged in lengthy negotiations with the President over the fiscal cliff in 2012, and then the debt ceiling in 2013 after which the US experienced a temporary government shutdown. The outcomes were: “reached a deal” in the fiscal cliff game (cooperative equilibrium), and “no deal” in the government shutdown game (non-cooperative, i.e. Nash equilibrium), at least initially.

In the latest installment of the same game, ongoing during September 2021, the US government narrowly avoided another shutdown last week, and this week Senate Republicans allowed the administration to temporary lift the ceiling until early December, thus postponing the crisis for at least two more months, when we will face yet another bargaining game.

Given that yesterday’s Senate vote hardly solved anything, the game will go on.

Let’s set it up.

First, the players.

President Biden and the Democrats on one side (although disunited over his infrastructure bill), and Senate Republicans on the other side.

Outcomes.

Reach a deal - debt ceiling is raised on a more permanent basis, Biden is free to go forward with his agenda.

Reach a deal where one party gives in - Either the Reps have to admit defeat to the Dems, or Biden has to agree to significantly cut his planned spending packages.

No deal - economic catastrophe, worst-case outcome that would derail the recovery

Payoffs and probabilities.

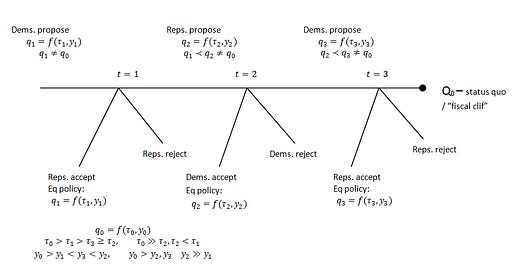

Defined by the following figure (taken from the fiscal cliff game where the status quo was the fiscal cliff; in today’s game the status quo outcome is credit downgrade and recession). Experienced game theorists might recognize this as an example of a Rubinstein bargaining game.

The goal of the game is to reach a cooperative equilibrium.

Democrats (the President) move first and propose policy q1 = f(τ1,y1), where τ and y are some combinations of tax and spending packages that require an increase of the debt ceiling due to more borrowing required to fund the package. Both are better alternatives than the status quo outcome. If the Republicans accept, this is the equilibrium policy and the deal is reached, with Republicans accepting fully and making no amendments. If they reject then we enter period t = 2.

In period 2, Republicans move first and set their policy proposal to be lower than τ1 and y1. If the Democrats accept and make no amendments, the equilibrium policy is reached at q2. If the Democrats reject, the game enters period t = 3. Each policy offered in the next round of negotiations is more preferred than the previously offered policy qo ≺ q1 ≺ q2 ≺ q3. The proposed policies can also be modeled as a deviation from each party’s optimal policy, but the intuitive result of the game is the same.

Period 3 is the last period since there is a time constraint given in the negotiations (it was initially October 14th, but now this has been postponed until December, meaning that the players changed the rules of the game - not cool for our model!). If until this period of negotiations no deal is reached then the status quo is applied, and the country goes through fiscal turmoil.

In the last period the Democrats again move first and propose a policy combination somewhere between their previous proposals. The Republicans now make the final move of the game. Their choice to give in and accept will depend on how close the Democrats were to their most preferred option. If they were rather far from it, the Republicans choose to reject the proposal and trigger the recessionary outcome.

Bottom line is, whatever the Democrats move forward as their final proposal before the deadline, the Republicans will have the final choice whether or not to accept it. And will have to carry the weight of triggering a recession.

Does this mean that the Reps have a bigger incentive to cooperate? Not really, since recessions are always bad for Presidents, regardless of who triggers them. Plus there is the looming shadow of Trump as a contender in 2024 who would love to use a recession narrative in his campaign (I can already see the new slogan: “I fixed it, they’ve messed it up”). One can arguably say that the Dems have more to lose with a non-cooperative equilibrium.

Ok, so what will happen?

You tell me! :)

We can introduce time discounting in the game and say that the closer we move to the deadline, the more likely it is for a party to reach a deal (especially the Dems). Or, we could think of this as a standard game of deterrence (or chicken game, hawk-dove, whatever you wanna call it). In that case it all depends on the strength of the commitment device.

One can claim that the Q0 outcome, the recession scenario, is enough of a commitment device to ensure a cooperative equilibrium. If we think of this game as a classical cold war nuclear game of deterrence, where both parties have a credible threat they are willing to use, but both of them know that triggering an action will lead to the least preferable outcome – a nuclear war, the commitment device is really strong and it prevents a non-cooperative Nash equilibrium. Because of a strong commitment device, both parties abstain from initiating an action.

This game, however, is a bit different, since the least preferable outcome is inevitable if the debt ceiling is not raised (in the nuclear game, the nuclear war can be prevented by doing nothing, while in this game a recession must be prevented by commencing an action). Knowing this, both actors should find a strong incentive to cooperate. Imagine if the debt ceiling deadline is the day when nuclear war starts. Then both actors have really strong incentives to prevent it.

So far the threat was, in fact, strong enough to at least force Republicans to postpone the deadline. This bought more time, but did not bring the actors near the final solution. However, given that Republicans blinked first, I would say that a cooperative equilibrium is a likely outcome of this Rubinstein bargaining game. Expect a few more political battles in December, but ultimately, the threat of inaction is too strong not to act upon it.

If you enjoyed this text, share it, and subscribe to the newsletter for more topical and interesting analyses. Also, the market prediction competition is next week, so…