The inflation conundrum: transitory or already gone too far?

Throughout the past year the Fed has made strong commitments to keep interest rates near zero until the end of 2023, during which they expect the labor market to fully recover. With the economy rebounding much more rapidly than expected - primarily due to mass COVID vaccinations and fiscal stimuli of the Biden administration - investors are starting to worry that the economy is already overheating. It feels like the whole COVID and post-COVID economic reality is one of very fast-paced developments. Usually it would take a few years of rapid economic expansion before higher inflationary expectations kick in. An even bigger worry for investors is a huge expansion of the Fed's balance sheet and massive money creation. This vast monetary expansion is already being linked to rising prices of commodities and agricultural goods, and consequentially other consumer goods. In the words of inflation hawks: inflation is already here!

Is it, though?

The money that the Fed created is not circulating in the real economy!

In one of my previous articles I tried to explain inflationary pressures using the employment-population ratio and the velocity of money, while also referencing to the huge level of excess reserves in US banks.

The point was to show that even though there is a huge, unprecedented level of money supply on the Fed's balance sheet, very little of that newly created money is being circulated in the real economy. The best proof of this is the velocity of money indicator, shown in Figure 1 (blue line), which is still at its all-time low.

Figure 1. Velocity of M2 money supply (M2 divided by nominal GDP), and the employment-population ratio

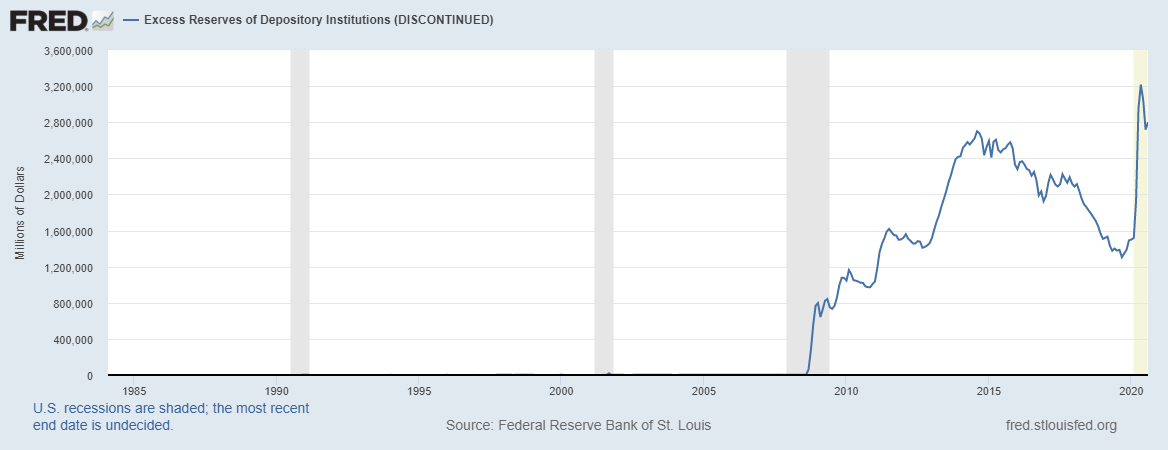

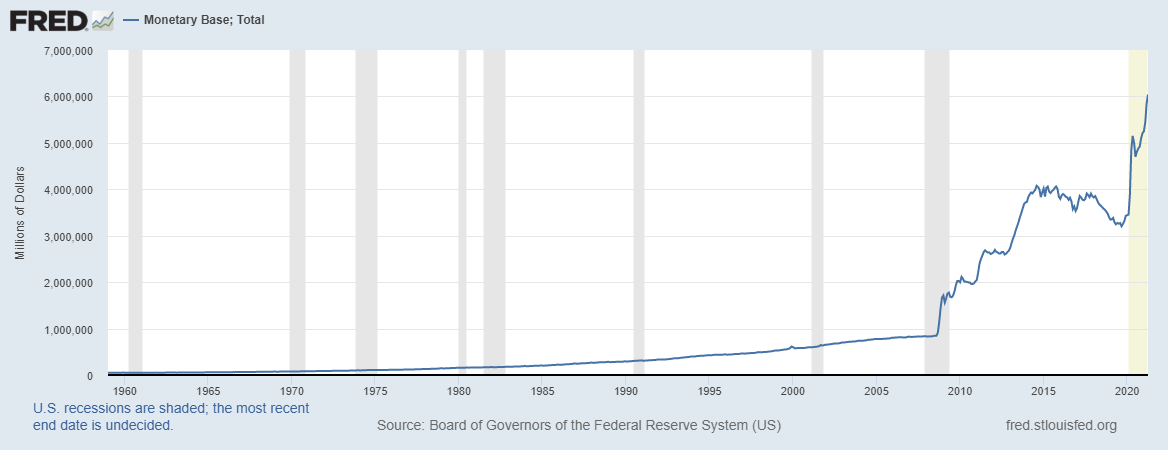

Furthermore, ever since the previous crisis the velocity of money is no longer correlated with the employment-population ratio. Typically these two indicators move in unison since more people having jobs means more spending, and more spending means that more money is circulating in the economy. However, ever since the Fed's QE policies of the past decade, that mechanism no longer seems to apply. The expansion of the money supply grew much stronger than nominal GDP, meaning that nominal GDP was not driven by excess money supply, or in other words: all this new money created is not being spent. It is sitting in between banks and the central bank, as Figure 2 clearly indicates. Note how Figure 2 looks exactly like the Monetary base of the Fed, shown in Figure 3. All that “printed” money just went into excess reserves.

Excess reserves of all depository institutions - the money held by banks in excess of what is required by regulators - are also at an all time high, even bigger than during the previous decade. Banks are hoarding cash on a massive scale, and this money is simply not present in the real economy.

Figure 2. Excess reserves of depository institutions (money held by banks in excess of what is required by regulations)

Figure 3. Expansion of monetary base

High commodity prices are a typical example of a supply & demand mismatch due to COVID

Another often cited reason for higher inflation expectations are rising prices of commodities and agricultural goods. But there is no evidence whatsoever that an expansionary policy of the Fed caused rising prices of commodities. In fact, the cause here is something else completely.

Let's start with oil. Oil prices even turned negative at one point in April 2020 ending that week at $16 a barrel, but have since rebounded to over $66 a barrel. However, we are used to seeing oil prices being volatile, so no one is pointing to them as an example of a +265% increase in price over the past year. People understand that oil prices go up typically due to a surge in demand or by artificial limitations of supply (like during trade wars).

Apply the same logic to all other commodities. Before COVID, companies had plentiful supply and kept large stockpiles of the commodities they use in production, like lumber, copper, platinum, iron, or agricultural goods like corn, wheat, cotton, etc. When the pandemic started and trade flows stopped for a few months, companies using these goods for production turned to their stockpiles. Many production companies, especially food production companies, continued working during the lockdowns (people still needed to buy stuff, services they could do without for a while, but not food). The biggest industry that halted production was the car industry, but most others did not go into lockdown.

A lot of these production companies relied on getting their raw materials from China and India, where trade was halted for a while. Many supply chains from these countries still have not been restored, so production companies in the US and Europe decided to shorten their supply chains and find other suppliers of commodities and agricultural products, those more close to their domestic markets.

As Western economies started reopening, the production companies kept buying even more commodities for two reasons: to keep up with the rising demand for their products from the rest of the economy which is now recovering, and to once again fill up on their stockpiles. Add the car industry into the equation, also aiming to shift their supply chains more close to home, and you can see that there was a clear surge of demand for all types of commodities.

On the supply side, the new suppliers are struggling to keep up with the massive demand, so naturally prices go up. Limited supply + huge demand = high prices. This is the basic economics principle that most people are disregarding. It has little to do with the Fed "printing money".

The Fed should stand its ground and not raise rates just yet

To recap, the reason prices of commodities and agricultural products are going up, which is in effect driving prices of goods based on these commodities, is the result of a pure mismatch in supply and demand - huge post-COVID demand, and a supply that is unable to keep up. On the other hand, all that money created by the Fed is not making its way into the real economy. It is sitting on banks' balance sheets.

Despite all this, inflation expectations are still running high. Long-run inflation expectations are best measured as the difference between the 10-year TIPS yield and the current 10-year T-Bill yield. The TIPS (inflation protected Treasuries) yield is at -0.83%, while the 10-year yield is at 1.61%. This would make long-run inflationary expectations standing at 2.44%, or slightly above the 2% long-term inflation target. This might not seem like much but inflation expectations are an important factor that drives current bond yields and hence markets in the short run. Investors are factoring in a rise in short-term interest rates, and hence mounting pressure on the Fed to increase the federal funds rate.

But there is a danger if the Fed raises rates prematurely. The Fed is not worried about inflation for a good reason: there are very little structural inflationary pressures out there. Yes, commodity prices will affect the prices of final goods and services but this will only be a temporary effect, not a permanent one. And if the Fed raises interest rates to try and address the temporary effect they risk slowing down the pace of recovery as well as the pace of rising employment numbers (which still, mind you, has not rebounded back to pre-COVID levels).

What to do? Hedge.

The impact of inflation expectations and rising yields on the stock market will be mixed. This is a fact given that investor expectations drive markets, regardless of whether the majority of investors are right or wrong. Some growth stocks that we have seen rise to astronomical highs during 2020 might be halted in 2021. On the other hand the focus has shifted to what was known as value stocks, or more likely - the recovery stocks; companies from heavily affected sectors (like tourism, airlines, or hospitality), and also banking stocks (which typically do well during times of higher inflation expectations).

In terms of investment advice, do what you should always be doing: hedge! If you think that the Fed is wrong, or that the aforementioned arguments do not hold, buy inflation protected assets like TIPS (which carry a negative yield right now - or better yet, buy the TIPS-backed EFT, TIP), or hedge a part of your portfolio by doing what Michael Burry is doing: buying TBT calls (betting on the decline of bond prices and rising yields), or TLT puts (same bet, reverse play). Or think of other assets that are likely to be affected by rising inflation expectations and hence rising bond yields (e.g. 2020 growth stocks like TSLA, ZM, ROKU, NIO, SPOT - all of which are already down 20-30% from their peaks). On the other hand, allocate more money into the recovery sectors or banking stocks. This trend of relocating from tech into banking and reopening sectors has been present for a while now.

Even if you're not worried about inflation at all, it still makes sense to take some profits from your tech holdings and use a part of those profits to hedge against the short-run rise of inflation expectations. After all, investor expectations are not always rational.