After a blow-off top 5% rally the week before, consolidations and pullbacks - like the ones on Thursday and Friday - are expected. No one knows when or by what magnitude, but they are expected.

However, have no doubt that we are still in a buy-the-dip environment. Each significant (>2%) pullback is a buying signal. The daily technicals are still very supportive (at the 20-day MA, where a cross would mean a 50-day MA provides additional support - plus still nowhere near 200-day MA), so don’t expect a crash coming into the end of year.

In fact, a year-end crash is still the least likely scenario.

We talked about this a month ago. It’s all about the end-of-year flows:

After the election (Nov 5th) and FOMC (Nov 7th), with both events passing, vol will naturally come down, and we will indeed get a buying opportunity for the end-of-year rally.

Why so convinced of the end-of-year rally? Because of the regular flows coming into the market, especially after a very good year for SPX (over 20% returns), which typically drives even more positive flows as we approach the end of the year.

Globally there is $250 *TRILLION* tied to the SPX directly, $40 trillion of which came in just this past year. We are talking about flows of $2-5 trillion monthly just as a result of regular passive investing.

Obviously downturns can and do happen, but as you might have noticed over the past few years, the sell-offs do not last long. Even the bear market of 2022 lasted much shorter than expected (as the recovery started already in Oct/Nov 2022). This is because of the flows. There is so much money invested in the market, and as the options market expands it provides the crucial support via the hedging of market makers.

Do keep this in mind over the rest of November and December. Also, keep in mind that narratives drive markets, especially during bullish periods. And right now, with Musk at the helm next to Trump, expect those two to drive very bullish narratives. Obviously narratives are not everything, but in bull markets, they can offer powerful support for rallies.

Therefore, in the medium term, a rally (markets grinding up) is still the most likely scenario. Something that will most likely last until mid/end January, until the flows evaporate and the danger zone begins. But we’ll touch upon that when the time is right.

The Goldman report

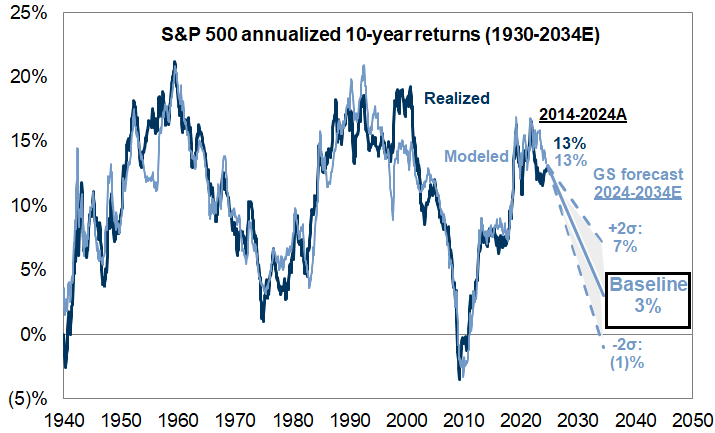

Today, I want to focus on a more long-term outlook, motivated by the report from Goldman Sachs that came out a few weeks ago (before the elections!), estimating an average annual S&P500 returns of only 3% in the next 10 years. Talk about a gloomy outlook!

To be fair, they give a range from -1% to 7% annualized returns (the 7% being the base case if they exclude the market concentration element, which has been immensely skewed towards Big Tech over the past decade). This is still a very conservative range given that SPX delivered an average annualized 13% during the past 10 years (and roughly 11% over the past 90 years). Why such a bearish outlook?

First of all, a clarification. An average annualized 3% return does not mean that SPX will be stagnant each year. Quite the contrary, it suggests that it can be quite volatile. In previous 10-year periods whenever the annualized rate of return was so low, much lower than the historical average, this would imply that a crash happened somewhere in between. Like the 1970s or the 2000s.

In other words, Goldman is expecting a market crash in the next decade. The low returns are therefore not attributable to a stagnation on equity markets, but are likely to underperform on average, after factoring in the crash. Their main conclusion is that the buy-and-hold strategy for equities will not be the best performing strategy and that it might fall short of bonds and other assets.

Is a market crash in the next 10 years that unrealistic? Not really. Especially when taking into account their arguments on valuations being rich, macroeconomic fundamentals favoring a contraction, and market concentration providing a high risk environment that will pull the index down just as sharply as it was pulling it up all these years.

And yes, each of these is indeed a strong argument. Based on adjusted P/E models, S&P500 valuations are extremely high, while market concentration is so skewed towards the Big Tech that even a modest correction in those stocks can cause a significant drawdown for the entire market. These are very high risks.

And then there is the macro environment. The report does not factor in the impact of the new presidential administration, but it does express fear over the Fed hiking cycle and whether they will indeed achieve a soft landing or just prolong the inevitable. As was the case in 1995 when the Fed declared victory too soon, and we saw a powerful bubble brewing in the next 5 years, only to see it burst spectacularly. Those years saw a very strong regression to the mean, and subdued average annual returns in the observed period.

Long term view

How likely is something like this to happen again? Recessions are notoriously impossible to predict.

But structurally some things are indeed very different. Specifically, interest rates. We got used to having very low interest rates and consequentially low inflation for almost 40 years (prior to COVID). Going back to that regime probably won’t happen any time soon. Higher interest rates are here to stay. Not as high as 4-5%, but certainly not 0% as they were throughout 2010s. Most likely expected to be around 2-3%.

This however creates problems for systems filled with debt. Back in the 1970s, when rates were at 10-12%, debt levels of both the public and the private sector were much much lower. For the past 40 years, as interest rates went down, governments and corporations have been refinancing debt with cheaper debt, year after year. It was so easy to incur new debt when interest rates were low or were on a secular downtrend.

This got exacerbated in the 2010s when interest rates were at zero most of the time, the term premium even turned negative, central banks invented QE, markets were making all-time-highs almost every year, and we saw massive technological expansion - this usually happens when interest rates are low. Looking at 800 years of interest rate movements, periods of low rates tend to fund innovation. Societies benefit.

However, this time we are left with huge, unprecedented peacetime levels of both public and private sector debt. Much bigger than the last time we faced high interest rates, high inflation, and geopolitical tensions (the 1970s). US debt-to-GDP is 4 times higher today than it was in the 1970s. Similar for many other countries, in Europe, and worldwide. This only means much higher share of budgets going for interest payments on debt (5-10% for some countries). Currently this isn’t an issue as governments are awash with cash, but it will not last. Fiscal pressures arising from this, in a period of a serious economic recession, would present a massive negative shock for public and corporate finances.

But the debt-driven growth model was necessary as Western economies kept producing at lower and lower levels of productivity. When you have an economic growth model driven by debt, you need low interest rates to keep fueling that growth. Or you need a massive productivity boost. That's what QE was for in the past decade, and again QE on steroids after COVID (central banks buying government bonds). It helped sustain the debt model, but it made the system structurally much much weaker. And dependent on central banks' and governments' explicit and implicit bailouts.

Having interest rates at 3% on average for the next 10 years could very well provide pressure that will break this cycle and cause a crash. To that end the Goldman projection would indeed come true. We would get a crisis in the same magnitude as in 2008 followed by austerity, tax hikes and all the social ills we had to go through in the early 2010s.

But this isn’t the only scenario. An alternative is that we get a miraculous and massive productivity boost in the form of a technological breakthrough - what else but AI.

If, through AI innovation or (still unobservable) derivatives of the AI revolution we see a massive increase of marginal worker productivity, this would then lower the pressure off fiscal and monetary policy to keep greasing the system. This happens slowly over time, and is not likely to pull us out quickly. But this is exactly the long term bet the markets seem to be making. AI will save the day. It is the dawn of a new era (alongside blockchain or crypto) and it will be the next industrial revolution thus providing the necessary productivity boost. Just like the Internet was in the 1990s.

Which of these is more likely? I would always bet on the second in the long run, but in the next 10 years? We might have to go through a crash first. Or even better, we first get to see the massive AI bubble pumped up, and only then we get the crash. When in the next 10 years? Not even Goldman Sachs knows that!

We at ORCA don’t really make such long-term forecasts, obviously. Ours is a weekly perspective and we adapt quickly. But we are aware of the macro environment, skew, and valuations. If these do indeed produce a negative shock, we are easily positioned to benefit from it. Our investors do not have to fear single digit average returns for 10 years, that’s for sure.

Thanks for reading!

DISCLAIMER: Neither the survey nor any of the contents of this website can act as investment advice of any kind. The results of the survey need not correspond to actual market preferences or trends, so they should be interpreted with caution. Oraclum Capital, LLC (Henceforth ORCA) is a management company responsible for running the ORCA BASON Fund, LP, and for organizing a survey competition each week, where it invites the subscribers to its newsletter (this website) to participate in an ongoing prediction competition. The information presented on this website and through the survey competition should under no circumstances be used to solicit any investment advice, nor is it allowed to be of commercial use to any of its readers. The survey and this website contain no information that a user may use as financial or investment advice. All rights reserved. Oraclum Capital LLC.